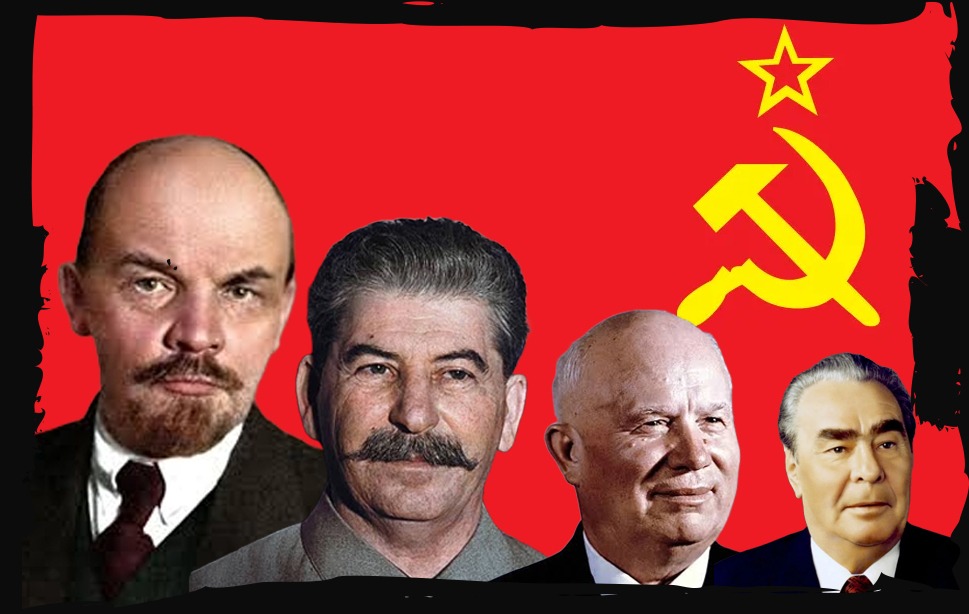

The global “war on terror” often portrays Palestinians as terrorists and human bombs, overshadowing their liberation struggle against settler colonialism. Palestinian progressive literature plays a crucial role in understanding this resistance and its impact on culture, illustrating the historical possibilities embodied in literature. Despite the current perception, a significant part of the original Palestinian resistance was rooted in revolutionary Marxist, secularist, and internationalist ideals, embodied by figures like George Habash and Ghassan Kanafani.

Western media’s characterization of Palestine as a terrorist breeding ground erases its rich history of progressive art, literature, and journalism. The first half of the twentieth century witnessed significant political, social, and literary changes in Palestine, leading to the emergence of the “poem of resistance.” Resistance poets like Mahmoud Darwish and Samih al-Qasim have used literature to raise awareness about the oppression faced since 1948. Israel’s direct occupation of large parts of Palestine since 1967 has forced Palestinians into an uncertain journey of displacement and exile. It is in this context that Ghassan Kanafani’s “The Land of Sad Oranges” serves as a powerful metaphor for the pain of exile and Nakba, portraying the emotional complexities of a displaced Palestinian family using oranges as symbols of homeland. Kanafani, a revolutionary Marxist, journalist, and political activist, founded the al-Hadaf newspaper and was brutally murdered by Mossad for his political activities at the age of thirty-six. “The Land of Sad Oranges” captures a family’s journey, highlighting the emotional bond with oranges and the constant tension between the land and the fruit. The story unfolds as a narrative of Kanafani’s childhood expulsion and deprivation from Palestine.

Colonization and exile

The narrator’s evolving consciousness reflects the broader changes in Palestinian families as the Israeli occupation expands. Kanafani skillfully weaves together themes of homeland, family, house, orange tree, and martyrdom, depicting the harsh realities of refugee status and loss. The drying and decay of oranges symbolize the distant memory of peaceful existence before becoming refugees. It is a journey that embraces political consciousness as its ultimate goal, or consequently the story departs. The first step, the short journey from Yafa to Acre, does not appear to be sad for the narrator child: ” When we left Yaffa to Akka, I felt no agony. It was like going from a city to another for a holiday. For several days, nothing painful happened. I was happy because this move gave me a nice break from school. ” The tragedy became clearer when the family was compelled to move from Acre to Lebanon due to an Israeli invasion: ” Things started to look differently when Akka was attacked. ” The narrative of the story begins to change as it moves from one scene to another. Many consider the story to be Kanafani’s autobiography. Some believe that the child who narrates the story is Kanafani’s childhood self. The narrator recounts the child’s feelings, swings, evictions, terror, and fear, i.e. Kanafani’s childhood expulsion and deprivation from Palestine. Kanafani portrays the orange to represent all other Palestinian families in the occupied territories in his story. Kanafani develops an emotional bond with oranges. When the family travels to Ras Nakur, the orange tree surfaces for the first time: ” …All along the way there were orange groves”. Kanafani is clearly referring at the narrative of why the orange hasn’t abandoned the Palestinians. Why do they perceive orange to be the ‘fruit of paradise’? Why do women cry when they buy oranges, and why does a father “cry like a baby” when he gaze at oranges? Kanafani expressed the narrator’s mental crisis through his tears when a family was forced to leave their land, which featured orange trees. In other words, the author stresses a constant tension between a piece of land and orange.

” Your father stretched out his arm, took an orange, stared at it silently, then burst into tears, just like a miserable, little child [..]In your father’s eyes were the reflection of all the orange trees he had left behind for the Israelis, all the clean orange trees he had planted one by one, glittered in his face. He failed to stop the tears that filled up in his eyes’’ Of course, the narrator of the story gradually realizes that he was forced to become a refugee as a consequence of such a disaster. He, too, has become one of thousands who have faced numerous challenges while seeking shelter and food. Any political crisis carries an economic and social impact. As a consequence of relocation, any community suffers enormous economic, social, political, and cultural losses. Every facet of their lives is made more difficult by the inevitable move. They gradually lost their distinct cultural traits. Immigration is an emotional representation of estrangement from distinct cultural roots, especially when they have been compelled to exile themselves from their homeland. A fearless desire abruptly took away the land he had known as his very own for a lifetime. There has always been a dialectical relationship that exists between immigration and culture, which Kanafani illustrates in his story. The story’s narrator slowly changes the child’s consciousness, and the child’s understanding of various forms of persecution — whether political or economic — develops. Even as a child, the child questions his personal responsibility: “Pain is beginning to weaken the child’s simple mind”.

Existential crisis

Kanafani emphasizes how the notion of the Palestinian Family is evolving as the Israeli occupation expands and land is increasingly evacuated. Other factors, such as family, are vital in establishing a social network based on socioeconomic links. Israeli attacks were rapidly crushing those aspects, and the family itself was thrust into an existential crisis. In this background, one can understand Kanafani’s statement to the narrator: “The happy, united family we left behind, land, house… The martyrs were killed while defending them. ’’ It is crucial that Kanafani is combining all of these ideas: “So, we have led this combination: the homeland, the land, the happy family, the house, the orange tree, and the martyr are all the same”. Kanafani depicts the drying and decay of oranges at the end of the story. In this way, he transforms orange into a distant memory while also serving as a representation of the peaceful existence that family members lived before becoming refugees. Orange is a metaphor for a personal, family, and national calamity in the story. It reflects the harsh realities of refugee status, despair, childhood deaths, and loss. Orange is adopted as a sign of memory retention.

Instead than repeatedly retelling the past, Kanafani emphasizes the lessons of looking at Palestinians’ lives through short narratives of life tragedies. Besides from instilling social consciousness in kids the left-wing writer has also hinted at how to resurrect the dead orange, i.e. return to its own land. Who says people who have been uprooted can’t write autobiographies?

Aftermath

During the 1948 conflict, more than 700,000 Palestinians were forced to flee from their homes and areas right after Israel’s revelation. For Palestinians, it’s a “nakba” or “disaster.” That nakba continues to exist today. Kanafani’s emphasis on short narratives of life tragedies aims to instill social consciousness in children and hints at the possibility of returning to their own land. The ongoing Palestinian struggle, marked by the Nakba of 1948, persists today, and the taste of the orange remains salty amidst the ongoing bloodshed.