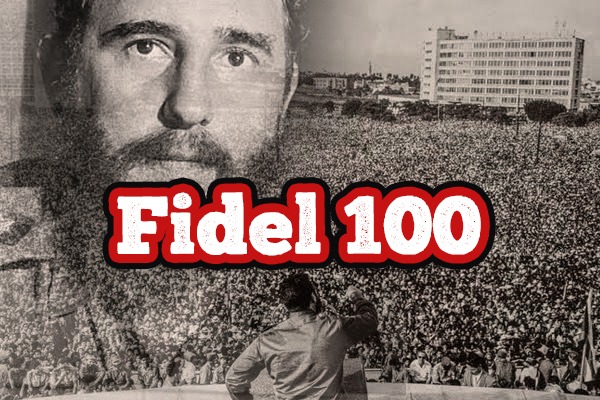

By the time Fidel Castro marched into Havana on January 1, 1959, the world communist movement was no longer the unified, surging force it had been at the end of the Second World War. Revisionism in Moscow had already cracked the ideological backbone of socialism. The capitalist world, momentarily thrown on the defensive in 1945, was regaining its confidence. In that hostile climate, Castro not only seized state power in the shadow of the United States — he held it for over half a century.

The Cuban Revolution is too often framed either as a romantic guerrilla saga or as an isolated national story. From a Marxist perspective, it is neither. It was a product of its global moment: a revolution born in the afterglow of socialism’s greatest triumphs, tempered in the fire of Cold War hostility, and sustained through sheer political will in an era of ideological fragmentation.

When the Red Tide Rose

To grasp Castro’s historical significance, we have to start in 1945. The Soviet Union, under Joseph Stalin, had shattered the Nazi war machine at a cost of over twenty million lives. The Red Army’s advance liberated Eastern Europe, while communist-led partisans struck decisive blows in Yugoslavia, China, Vietnam, and Greece.

For the first time in history, socialism was not a besieged outpost but a vast bloc stretching from Berlin to the Pacific. Newly liberated nations looked to Moscow not only for aid but for a model of industrialization, social transformation, and anti-imperialist unity.

In Asia and Africa, decolonization struggles drew strength from this socialist core. Even leaders outside the communist tradition — Sukarno in Indonesia, Nasser in Egypt — recognized the Soviet Union as the indispensable counterweight to imperialism. For the world’s oppressed, socialism was not an abstract ideal; it was a living, advancing force.

Marxism on Leadership

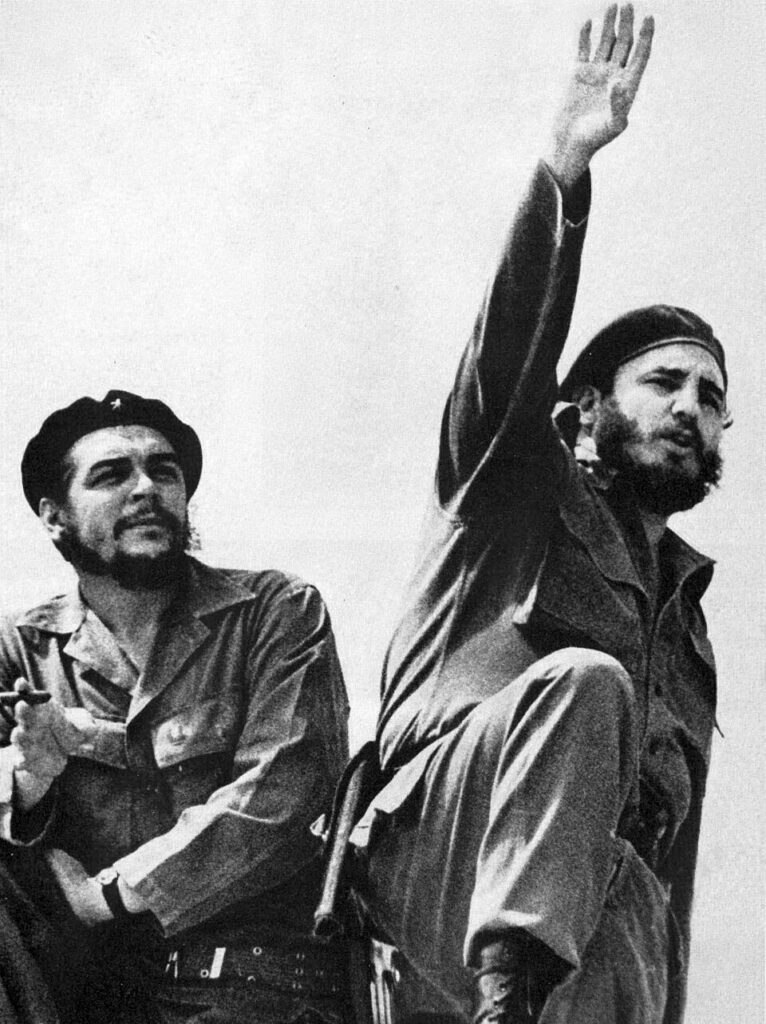

Marxism rejects the “great man” theory of history, but it also recognizes that certain individuals, arising at the intersection of mass movements and historical necessity, can accelerate the transformation of society. The bourgeois-democratic revolutions had their Cromwells, Washingtons, and Robespierres; the socialist revolutions produced their Lenins, Stalins, and Maos.

In India’s anti-imperialist struggle, figures like Subhas Chandra Bose and Bhagat Singh revealed, in different ways, the influence of Marxist thought on militant nationalism. Globally, the period between 1917 and 1953 was one in which the communist movement could produce leaders of world-historical stature, rooted in theory and tested in struggle.

1956: The Great Retreat

That era ended abruptly in 1956. Nikita Khrushchev, solidifying his grip on Soviet power, used the 20th Communist Party Congress as a platform to repudiate Stalin. It was not merely a personal attack; it was a political turn.

By discarding Stalin’s analysis of imperialism, war, and socialist construction, Khrushchev replaced revolutionary confrontation with the rhetoric of “peaceful coexistence” — not as a tactical breathing space, but as a long-term accommodation with capitalism. The consequences were catastrophic.

The disciplined unity of the communist movement fractured. Parties split into pro-Moscow and pro-Beijing camps, often engaging in sterile factional battles while losing their mass base. In Europe, once-mighty communist parties drifted toward reformism and electoralism. In the Global South, national liberation movements found the socialist camp less reliable and less ideologically coherent than before.

It was into this turbulent, weakened, and divided movement that Fidel Castro’s revolution burst onto the stage.

The Cuban Detonation

When Castro and his guerrillas toppled the Batista dictatorship in 1959, they did so less than 100 miles from U.S. shores — in a hemisphere Washington considered its private preserve.

Cuba’s revolution was not scripted in the orthodox Marxist fashion. It began as a nationalist-democratic struggle against a corrupt dictatorship, and only under the pressure of U.S. hostility did it move toward socialist measures: land reform, nationalization, and the expropriation of foreign capital.

But once the die had been cast, the course was irreversible. Castro aligned with the Soviet Union, secured military and economic aid, and declared Cuba a socialist state. The revolution’s survival through the Bay of Pigs invasion, the Missile Crisis, and decades of blockade was a testament to the resolve of its leadership and the mobilization of its people.

A Marxist View of Castro’s Role

From a Marxist standpoint, Castro’s genius lay in connecting national liberation to social revolution. He grasped — whether instinctively or through the hard lessons of U.S. aggression — that political sovereignty meant little without dismantling capitalist property relations.

His government’s achievements were undeniable: literacy campaigns that eradicated illiteracy, a public health system envied across the Global South, and a foreign policy that sent Cuban doctors, teachers, and soldiers to aid liberation movements from Angola to Venezuela.

Yet Marxists must also acknowledge the limits imposed by Cuba’s conditions. As a small, export-dependent economy, Cuba was structurally reliant on the Soviet Union, which created vulnerabilities when that support vanished in 1991. Moreover, while the revolution developed a socialist state apparatus, it never fully resolved the question of ideological clarity — a problem intensified by the broader crisis of Marxism-Leninism after 1956.

Indian Marxist leader Shibdas Ghosh offered a characteristically sober assessment: Castro was a courageous revolutionary whose defiance of imperialism inspired millions, yet he operated in an era when revisionism had already weakened the theoretical unity of the world movement. For Ghosh, this meant Castro’s leadership, while historic, was shaped and partly constrained by the absence of a coherent, centralized Marxist-Leninist direction internationally.

Castro in His Own Time

In the 1960s and 1970s, Castro was the undisputed voice of Third World defiance. In the Non-Aligned Movement, he pushed for anti-imperialist solidarity that went beyond diplomatic neutrality. In the United Nations, he denounced the economic order that kept the Global South in dependency.

Cuba’s military interventions were among the most striking examples of proletarian internationalism in the late 20th century. In Angola, Cuban forces helped defeat the South African apartheid regime’s military in the battle of Cuito Cuanavale — a blow that accelerated Namibian independence and the dismantling of apartheid itself.

From a Marxist perspective, these actions placed Cuba in the vanguard of anti-imperialist struggle, even as the socialist bloc it depended on was showing cracks.

The Present Generation’s Lens

Today’s generation faces a global order reshaped by neoliberalism, the collapse of the Soviet Union, and the rise of new capitalist powers. In this world, Fidel Castro’s legacy is double-edged.

For young activists, especially in Latin America, he remains a symbol of revolutionary courage — proof that a small nation, committed to socialism, can resist the greatest imperialist power in history. Cuba’s record in education, health care, and disaster relief still shames the capitalist nations of the hemisphere.

But for Marxists, the Cuban experience also underscores the necessity of ideological firmness. Without the theoretical unity and strategic clarity of a strong international communist movement, even the most heroic revolutions must navigate isolation, economic siege, and the temptations of compromise.

Lessons for Marxists

The Cuban Revolution demonstrates two core truths of Marxism-Leninism:

- Seizing the moment matters. Revolutions are made not in ideal conditions but in the contradictions of the present. Castro acted decisively in a time of global retreat, and that decision reshaped the politics of an entire hemisphere.

- Theory is a weapon. Military victories and political will must be anchored in scientific socialism to withstand the long war against imperialism. Without it, gains can be eroded — not always by direct assault, but by the slow pressure of economic dependency and ideological drift.

An Unfinished Chapter

Fidel Castro died in 2016, but the Cuba he built still stands — battered, blockaded, yet unbowed. The island remains a thorn in the side of U.S. imperialism, a living reminder that alternatives to capitalism are possible.

From a Marxist standpoint, Castro’s life is not a closed chapter but part of an ongoing narrative: the struggle to rebuild a revolutionary movement capable of uniting the global working class, resisting imperialism, and constructing socialism on firmer, clearer foundations.

The task for today’s Marxists is not to romanticize Cuba’s survival, but to learn from it — to combine Castro’s audacity with the theoretical clarity that the 20th century’s defeats made so urgent.