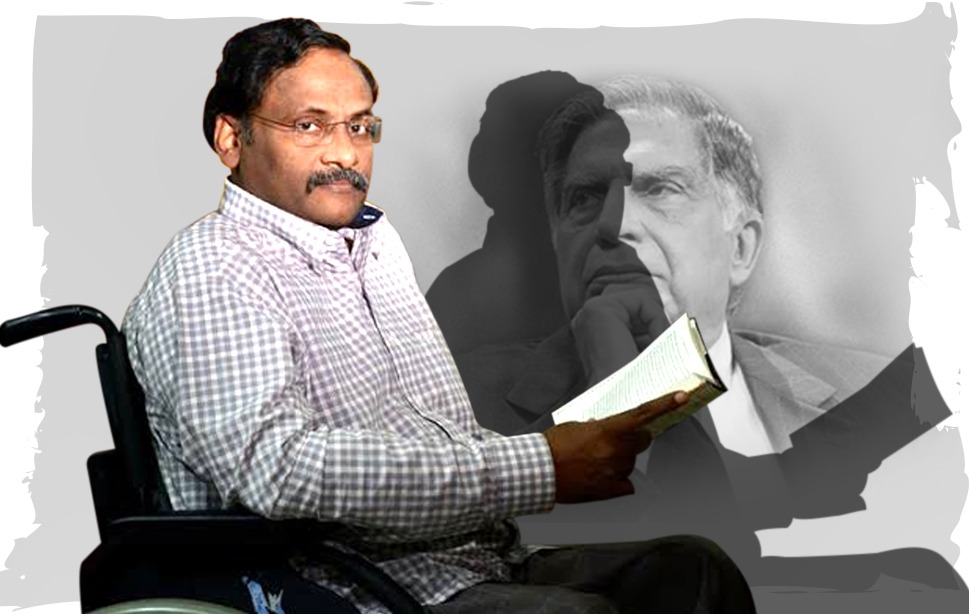

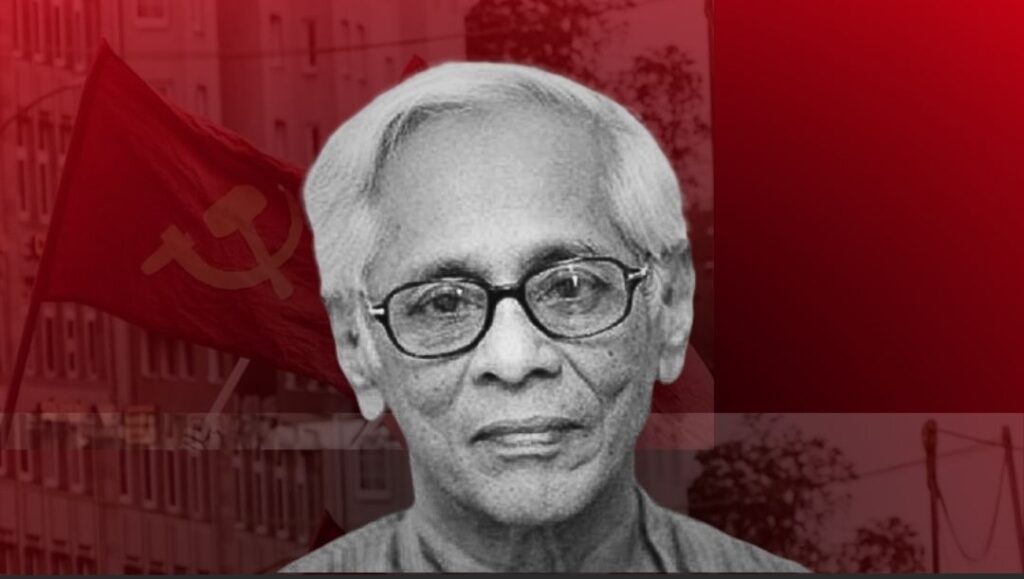

The recent deaths of Ratan Tata and G. N. Saibaba highlight a striking contradiction in how society mourns. Tata, a well-known businessman, was widely celebrated as a national icon of progress and humility while Saibaba, a lifelong staunch human rights activist, passed away with little recognition. This contrast in how these figures are remembered reveals deep-seated biases and hypocrisy where society glorifies wealth and power while marginalizing or punishing those who challenge exploitation. A closer examination of these deaths from a Marxist perspective reveals how the state and corporate interests work hand-in-hand to suppress dissent and protect capital and also shape the public conscience.

The Celebrated Businessman and the Forgotten Activist

Ratan Tata, the former chairman of the Tata Group, is often viewed as a symbol of Indian corporate success and social responsibility. The Tata Group’s vast business empire includes sectors like mining, steel, and automobiles, contributing significantly to India’s industrial growth. However, the growth of this empire has not come without a cost, particularly for resource-rich regions inhabited by Indigenous Adivasi communities. Corporate projects have frequently led to forced land acquisition, displacement, and environmental destruction. A notable example is the 2006 incident in Kalinganagar, Odisha, where Adivasis protesting against land acquisition for a Tata steel plant were met with state violence, resulting in the deaths of at least 13 people. Such events are not anomalies but part of a larger pattern where state power is used to suppress resistance of the marginalized and facilitate corporate expansion.

G. N. Saibaba, on the other hand, was dedicated to defending the rights of these very communities. As a professor at Delhi University and a vocal activist, Saibaba fought for Adivasi land rights and opposed the takeover of tribal lands for mining. He saw firsthand the harm caused by corporate encroachment on Indigenous land and spoke out against it, making him a target for state repression. In 2014, Saibaba was arrested under the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act (UAPA), a controversial law often used to silence dissent. Despite being wheelchair-bound due to polio since childhood and suffering from various health issues, he had to spend more than eight years in jail, where he was denied adequate medical care and subjected to harsh conditions. This was not merely a failure of the system; it was a deliberate act of repression to crush a voice that challenged powerful interests.

An Institutional Murder: The State’s Role in Saibaba’s Death

Saibaba’s death was not a result of natural causes; it was an institutional murder, orchestrated through years of state neglect and cruelty. During his imprisonment, he was denied basic medical attention, despite his critical health condition. The prison system, which is already infamous for its inaccessibility for people with disability and inadequate healthcare, became a death trap for Saibaba. The state’s refusal to provide proper treatment, coupled with the harsh conditions of imprisonment, contributed directly to the deterioration of his health. This deliberate neglect was not accidental but a calculated part of the state’s strategy to silence dissenting voices by any means necessary.

Activists like Saibaba, who spoke out against the dispossession of Adivasis and the environmental damage caused by mining, were seen as threats to the interests of powerful corporates, including the Tata Group. The use of draconian laws like the UAPA to imprison such individuals reflects how the state criminalizes resistance while protecting the interests of capital.

The Glorification of Ratan Tata’s “Humble” Lifestyle

Ratan Tata’s image is carefully curated to present him as a humble and charitable figure, despite his vast wealth. Stories of him driving himself or living in a modest house are highlighted in the media to paint him as a “people’s businessman.” This narrative serves to mellow down Tata Group’s violent practices and distract from the systemic exploitation that enabled the accumulation of his wealth. The surplus extracted from the labor of Tata Group’s workers and the resources taken from tribal lands fueled the company’s growth, generating the profits that allowed for philanthropic endeavors. In this way, acts of charity are used to sanitize the darker aspects of corporate expansion, presenting Tata as a benevolent figure rather than a beneficiary of a system that prioritizes profit over people.

The myth of the humble billionaire not only serves to legitimize wealth accumulation but also obscures the underlying inequalities that sustain it. While the media emphasizes Tata’s “simple living,” it downplays the fact that his companies were involved in projects that contributed to the displacement of communities and the exploitation of natural resources. This glorification reflects the successful efforts to shape public conscience and popularize celebrating individual acts of charity while ignoring the structural issues that create poverty and inequality in the first place.

State Repression to Benefit Corporate Interests

The state’s role in protecting corporate interests is evident in several instances where repression was used to suppress opposition to projects involving Tata Group. The Kalinganagar incident is just one example of how the state has been willing to use violence to facilitate corporate expansion.

In Bastar, Chhattisgarh, military force has been employed to suppress local opposition to mining projects, including areas where Tata Steel had exploration licenses. The militarization of these regions under the pretext of fighting insurgency has often targeted Adivasi communities who resist land acquisition, resulting in human rights abuses such as forced displacement and extrajudicial killings. That being said, it doesn’t come as a surprise that the Tatas were one of the biggest funders who gave money to Fascist BJP through electoral bonds which the Supreme Court later ruled as being unconstitutional.

In Singur, West Bengal, the government used coercion to acquire farmland for a Tata Nano car factory, leading to widespread protests by farmers who were unwilling to give up their land. Although the project was eventually abandoned, the state’s approach to land acquisition indicated its readiness to prioritize corporate interests.

These examples show that the Indian state, through its legal and military apparatus, acts as an enabler of corporate exploitation, suppressing any resistance that poses a threat to the profits of companies like Tata Group.

The Use of UAPA and the Criminalization of Dissent

The Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA) is a tool used by the state to criminalize dissent and silence activists. The law’s vague definitions allow for the imprisonment of individuals under charges of “anti-national activities” without trial. In G. N. Saibaba’s case, the UAPA was used to frame him as a threat to national security, despite his activism being focused on defending the rights of oppressed communities. His arrest and imprisonment sent a clear message to other activists: any challenge to corporate interests or state policies could result in severe repercussions.

This kind of repression is not limited to Saibaba but affects numerous activists, journalists, and human rights defenders across the country. By using laws like the UAPA, the state ensures that resistance is met with harsh punishment, effectively discouraging others from speaking out. This repression benefits corporations by reducing the opposition to projects that would otherwise face significant local resistance, particularly in resource-rich areas.

Hypocrisy in Public Mourning: Whose Lives Are Valued?

The stark difference in how Ratan Tata and G. N. Saibaba are remembered exposes a deep-seated hypocrisy in society. Tata’s death was widely mourned, with tributes praising his contributions to the nation. The media celebrated his “humble” lifestyle and philanthropic efforts, conveniently overlooking the exploitation and harm associated with his corporate empire. On the other hand, Saibaba’s passing was met with silence, even though his life was dedicated to defending the rights of those most affected by corporate greed and state violence.

This disparity reveals a societal bias shaped by capitalist propaganda that values wealth and power over justice. While Tata is celebrated for his role in building a business empire, the struggles and sacrifices of Saibaba, who fought against the injustices perpetuated by such empires, are forgotten. It reflects a moral failure to recognize the value of those who challenge exploitation and stand up for the oppressed. This bias is further reinforced by the media, which plays a significant role in shaping public perception by glorifying corporate leaders and ignoring the voices of dissenters.

Challenging the Ideological Hegemony

The contrasting responses to the deaths of Ratan Tata and G. N. Saibaba are not just about individual legacies but represent the broader ideological hegemony in society. The state and the media play a crucial role in shaping how we perceive figures of power and resistance. Corporate leaders are framed as “nation-builders” and “philanthropists,” while activists challenging the system are branded as “troublemakers” or “anti-national elements.” This narrative not only serves to protect the interests of the ruling class but also erases the struggles of those who resist oppression.

To challenge this ideological hegemony, it is essential to recognize the systemic injustices that underpin wealth accumulation and the repression of dissent. The glorification of corporate figures like Tata must be questioned, and the contributions of activists like Saibaba must be acknowledged. A society that truly values justice cannot afford to ignore the sacrifices of those who fight against exploitation and inequality.

Moving Toward Justice: Building Solidarity and Continuing the Struggle

To honor the memory of G. N. Saibaba and others like him, it is vital to continue their struggle for justice. This means resisting the state’s attempts to criminalize dissent and challenging the structural inequalities that allow corporations to exploit resources and displace communities. Solidarity with those who resist state and corporate violence is not just a moral obligation but a necessary step toward building a more just and equitable society.

The fight for justice for Saibaba is not just about resisting state repression; it is about challenging the entire system that allows such repression to occur. His death should not be seen as the end of his struggle but as a call to action for all those who believe in the fight for human dignity. By recognizing and confronting the contradictions a society, that rewards compliance with the status quo while punishing those who fight for justice, remembers figures like Tata and Saibaba we can begin to build a society that values human dignity over profit.