Just a few months back. It was a pleasant March evening in Kolkata, and I was sitting inside the century-old library building of ‘Bangiya Sahitya Parishat’, going through nearly-brittle pages of some copies of ‘Benu’ magazine – the short-lived mouthpiece of Bengal Volunteers, a secret revolutionary organization operating in Bengal in late 1920s and early ’30s.

Suddenly, I came across an editorial, entitled ‘Bilater Nirbachon’ (English: Election in Britain), published in the Ashar issue of 1336 Bengali calendar year (June-July of 1929). Originally intended for teenagers, ‘Benu’ set its benchmark in covering global politics. A nicely crafted report featuring deep insights and outspoken comments, the editorial started as this:

“Bilater nirbachon sesh hoiya gelo. Shromik Dol joyjukto hoiyache, Ramsay McDonald Prodhan Montri nijukto hoiyachen – ar Kaptan Wedgwood Benn Bharat Sochib er pode brito hoilen.” Translated, it would read: “The general election in the United Kingdom just ended. The Labour Party emerged victorious. Ramsay McDonald has been elected Prime Minister – and, Captain Wedgwood Benn has been appointed as the Secretary of State for India.”

The 1929 United Kingdom general election was significant for several reasons. First of all, it was held just three years after the historic ‘9-day general strike of 1926’, with memories being still fresh. Unemployment was on the rise across Britain. It was also the first election where women aged between 21 and 29 earned their right to vote. Moreover, the following cabinet would witness the appointment of trade unionist and women’s rights activist Margaret Bondfield as the Minister of Labour – the first-ever woman cabinet minister of Britain.

The Labour Party, though received fewer votes compared to the Conservative Party (37.1% compared to Tories’ 38.1%), outnumbered their main opponent by 27 seats (287 seats for the Labours, 260 seats for the Conservatives). However, they still fell 21-seat short of single majority, and thus Ramsay McDonald, in his second term as the Prime Minister, had to form another minority Labour government.

The situation was tense in the Indian subcontinent. British betrayal at the end of the WW1 led to nationwide discontent. Mahatma Gandhi emerged as the undisputed leader of the deprived mass. Armed resistance gained momentum at the same time. But, this decade would witness a more significant development in the political arena of the country, which would have a long-lasting influence in the latter half of the century, and that is, communism.

Five years after the formation of the émigré communist party in Soviet’s Tashkent, Communist Party of India (CPI) was formed in 1925 at Cawnpore (now Kanpur), the same city where leading communist politicians were arrested under the Cawnpore Bolshevik Conspiracy Case just a year ago. The growing influence of the Communist International further worried the British Government. In March 1929, just two months before the general election in discussion here, another conspiracy case was initiated by the Government, this time at Meerut, where a large number of trade unionists and socialist leaders, including three British nationals, were tried and jailed.

The Labour Party, being a party that had historically represented trade union causes, was perceived as a sympathizer to the Indian freedom struggle (interestingly, India would later achieve independence during the tenure of Clement Atlee, a Labour Prime Minister). But, the reality was far from truth at that time. Ramsay McDonald made it quite clear that he was ‘a Britisher first and socialist last.’ In the editorial, ‘Benu’ clearly stated that it would be stupid of moderates to think that British Government would now consider the matter of self-governance with seriousness. They even pointed out the passing of the draconian Bengal Criminal Law Amendment Ordinance of 1924, passed during McDonald’s first minority government to suppress the rise of armed nationalism against the Raj post-1922. In contrast, they regretted that Shaklatvala could not make it to the Parliament this time.

Shapurji Dorabji Shaklatvala was a remarkable figure in British politics. He was not only the first Labour MP of Indian origin but also one of the few members of the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) to serve as an MP. In the 1924 general election, where the Conservatives secured a thumping majority of 412 seats (308 seats needed for majority) and Labour and communist candidates performed poorly, Shapurji contested as a communist candidate without the official endorsement of the Labour Party from Battersea North, but still managed to win his seat.

Two years later, his role in the general strike led to his arrest. At the time of the 1929 election, he was active with the League against Imperialism and Colonial Oppression. He lost his seat to the Labour candidate William Sanders, which effectively ended his parliamentary career. So, from an Indian revolutionary perspective, the 1929 election was not encouraging.

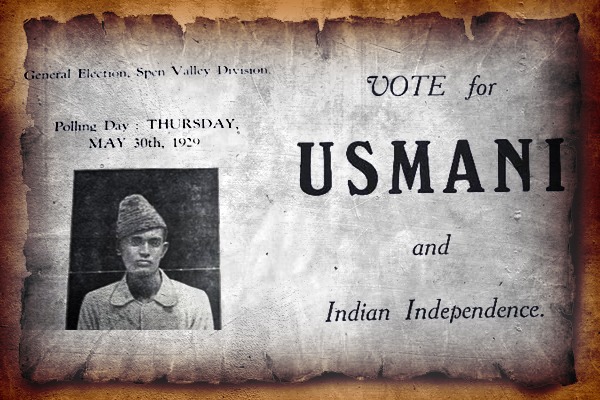

However, that was not all. There was one silver lining, at least for the juvenile Indian communist movement. Shaukat Usmani, a jailed leader under the Meerut Conspiracy Case was fielded as a candidate at the Spen Valley constituency, that too against a heavyweight Liberal John Simon (the same person who chaired the infamous all-white ‘Simon Commission’ that faced nationwide protests in India just the previous year). Referring to the fact, the editorial column of the 1336 Jaisthya issue of Benu (May-June) sarcastically commented: “How could the authority breathe if they are being kept busy from all the sides.”

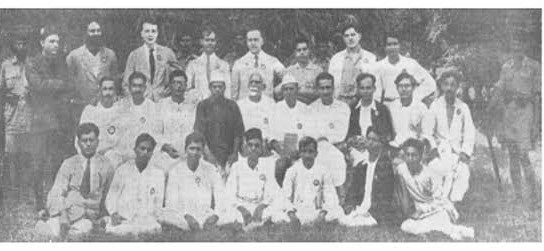

Born into a traditional Usta art family of Bikaner, Rajasthan, Shaukat Usmani (1901-1978) was a pioneering communist leader with a life of colourful experiences. At the age of 18, he was on his way to Turkey to fight against the Imperial British forces with several other young men, but later they changed their minds and turned to Russia instead. The Congress of the Peoples of the East, held in September 1920 at Baku, Azerbaijan, paved the way for the Communist International to connect itself with anti-colonial struggles in the colonies. This would have a lasting impact on the young Shaukat. He later received warm welcoming on the Soviet soil, and got enrolled in the Communist University of the Toilers of the East (KUTV) to study world history, Marxist history and historical materialism.

He returned to India in January 1922, and soon began working in his capacity. His experiences abroad were getting published, and thus he became a prime suspect under the British radar. Along with Shripad Amrit Dange, Manabendranath Roy, Nalinibhushan Dutta Gupta, Muzaffar Ahmad, Singavarelu Chettiar and Ghulam Hussain, Shaukat Usmani was charged under the Cawnpore Bolshevik Conspiracy Case on 17 March 1924. He was released three years later, but again imprisoned under the Meerut Conspiracy Case in 1929.

The second case was unique in its way as three British nationals were also arrested. Of them, Ben Bradley and Phillip Spratt were CPGB members who arrived in India to assist their Indian comrades in organizing workers’ unions, while Lester Hutchinson was professionally a journalist of radical outlook and hailed from a communist family. Arrest of them, as British communist journalist Robin Page Arnot pointed out in ‘Labour Monthly’, “destroyed once and for all the jingo picture of ‘black man’ versus ‘white men’, of ‘Asiatics against Europeans’ and showed the true line of cleavage in the fight of the oppressed of both nations against the oppressors.” It was against this backdrop of the fact that communists of both the colony and the colonizer were fighting a common enemy of imperialism, Shaukat Usmani received a telegram from the CPGB with a request if he could accept their nomination.

He took no time in accepting their proposal, and though faced with great difficulty, he managed to send an appeal to the common British people, which read: “I wish, though separated from you by 6000 miles and prison bars, to place before an appeal. I appeal to you, not on my own behalf but of the 300 million toiling masses of India.”

Shaukat Usmani, quite expectedly, did not win the seat. David slaying Goliath-like fairy tale never happened. Instead, it was a neck-to-neck fight between John Simon (who received 22039 votes) and the Labour candidate Herbert Elvin (who received 20300 votes). But, his candidature reflected a much broader spectrum, something that could not be explained by the mere 242 votes he received. Not to forget, he was the only Indian candidate from British India to contest in the Parliamentary elections while residing in India, and that too in a prison.

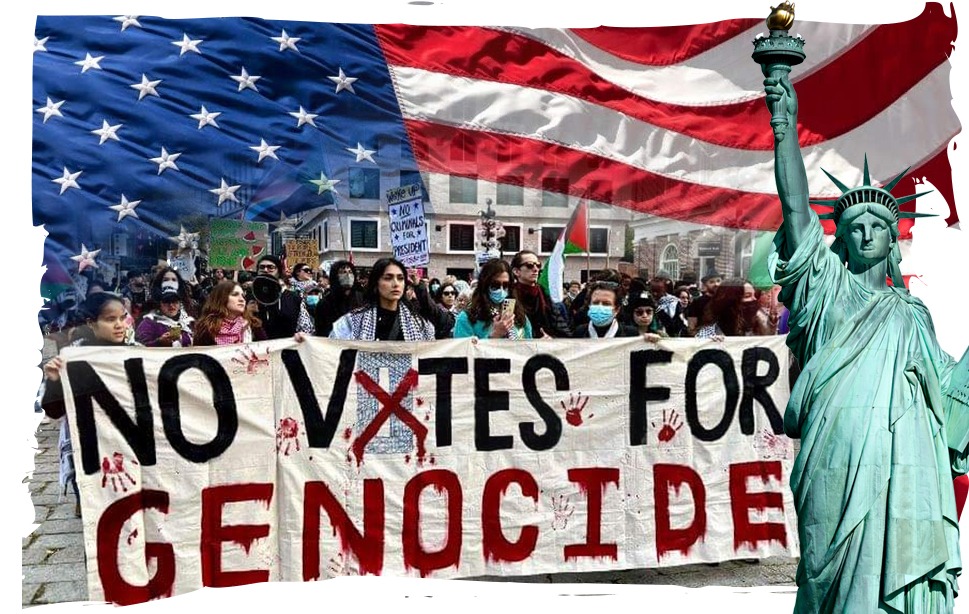

With the 58th General Election just over, the Labour Party ending a long 14-year Conservative rule, leftist Jeremy Corbyn (expelled from his party, just as Shaukat Usmani was expelled from CPI in 1932) having won as an independent candidate, and the Indian leftist movement having lost significant grounds over the last few decades, it is important that we re-read Shaukat Usmani, rediscover the internationalism they practiced, reinvent the legacy they had left.