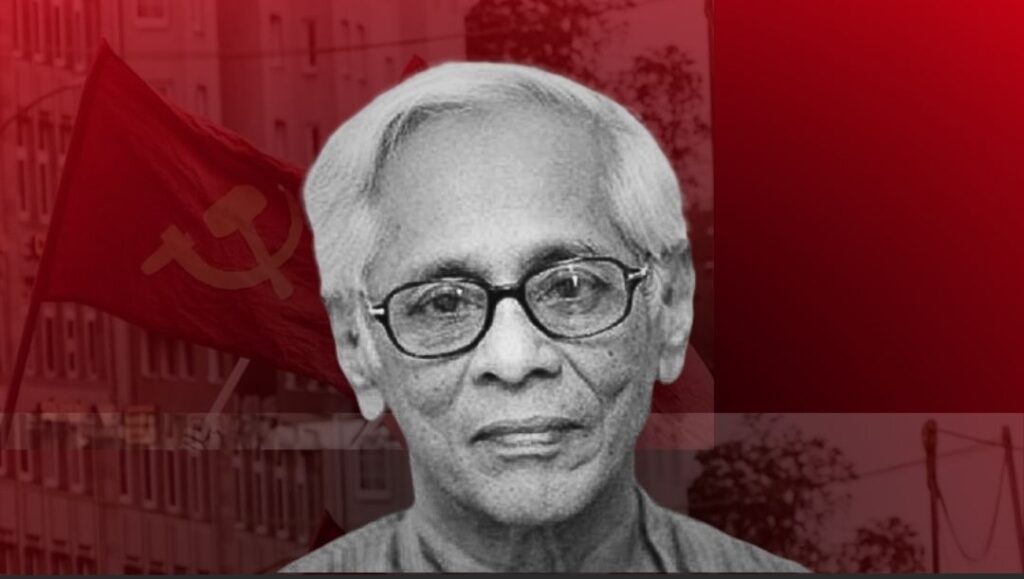

The Communist governments in Kerala have consistently been a significant topic of discussion on international platforms, primarily due to their accomplishments and their resistance against right-wing opposition. Kerala has notably suffered from the misuse of Article 356 of the Indian Constitution. The dismissal of the first Communist Party of India (CPI) government, headed by E.M.S. Namboothirippad, marks a regrettable and dark episode in India’s modern history.

The infamous Vimochana Samaram (which translates to “Liberation Struggle”) continues to be hailed by the Congress party and other right-wing groups as a victory against communism. However, this conservative movement and the ousting of the CPI government in July 1959 dealt a serious setback to Kerala’s renaissance ideals and progressive initiatives. The progress and achievements attained by the state and its citizens through intense effort and struggle were reversed in a crude, unethical, and deeply objectionable way.

Kerala holds the distinction of being one of the first few places in the world where a communist party ascended to power through democratic elections. The CPI’s electoral success was a significant shock to the Congress party, which was the ruling party at the Union level at that time. Having formed governments in multiple states, Congress regarded itself as the dominant political force. Therefore, the election outcome in Kerala was a considerable blow to their supremacy. The reactionary elements within Congress, aided covertly by the CIA, were deeply disturbed by the widespread display of communist influence in such a small state. They were unable to accept that despite severe repression and widespread anti-communist hysteria, the CPI managed to form the government. A close examination of the vote shares reveals that although Congress had a greater share of the popular vote, it failed to win enough seats to achieve a simple majority. Conversely, the CPI secured more seats by effectively leveraging independent candidates, even though their overall vote share was lower.

The mastermind behind this electoral triumph was veteran CPI leader M.N. Govindan Nair, famously nicknamed the “Khrushchev of Kerala.” As a grassroots leader, he understood the popular sentiment and designed a candidate selection and campaign strategy that proved decisive.

Achutha Menon’s Budget: The Engine of Change

Central to the CPI’s vision was C. Achutha Menon, who served as Kerala’s first Finance Minister. On June 7, 1957, he introduced the state’s first-ever budget, which laid the foundation for numerous progressive policies aimed at empowering marginalised communities. This budget focused on land reforms, workers’ rights, and equal access to education, directly challenging the entrenched power of feudal landlords and religious establishments. These reforms were not just bureaucratic adjustments but represented a fundamental move toward a more just and equitable society.

The Spark Points

The introduction of the Education Bill and the Agrarian Relations Bill acted as key triggers that mobilised conservative and reactionary forces. On December 4, 1958, a conference of Catholic bishops convened in Bangalore, attended by the Vatican’s ambassador to India, James Robert Knox. Interestingly, the meeting was not held to discuss purely religious matters. Instead, they seriously debated the “material and spiritual” strategies to topple the Communist government in Kerala. According to a report in the Indian Express published the following day, the bishops dedicated a significant part of their fifty-hour discussions to the perceived communist threat in India, particularly focusing on Kerala. They expressed strong opposition to the Kerala Education Bill, criticising it vehemently.

The Kerala Agrarian Relations Bill, introduced at the end of 1957, had sweeping consequences. It imposed a land ceiling of 15 acres of wetland per family, guaranteed security of tenure to all tenant types, and stipulated that tenants would gain ownership rights after paying twelve times the contract rent. Furthermore, landlords’ ability to reclaim land was severely limited. These provisions sent shockwaves through the ranks of the large landlords and plantation owners, as the bill had the potential to dismantle feudal structures.

Following the enactment of these bills, an unlikely coalition formed among communalists, caste-based factions, and right-wing groups. Congress leader Panampilly Govinda Menon is credited with coining the term “Vimochana Samaram” or “Liberation Struggle” to describe this movement.

The Fallout

The CPI government hesitated to retract these progressive bills, refusing to abandon their pro-working-class stance. This intransigence led to escalating violence, with rioters clashing with police forces. Police shootings occurred in places such as Angamaly and Chandanathope. In Angamaly, seven individuals, including a pregnant woman named Flory, were killed by police gunfire. In Chandanathope, police opened fire on cashew workers affiliated with the Revolutionary Socialist Party (RSP). These tragic events only intensified the agitation. On July 30, 1959, citing the volatile situation in Kerala, the President of India dismissed the EMS government. Newspapers like Deepika and Manorama played a crucial role in amplifying anti-communist sentiment among the populace, which influenced the outcome of subsequent elections in favour of Congress and its allies.

Influence of the Church and NSS

Another pivotal conference of Catholic bishops took place in Ernakulam on March 18, 1959, aiming to devise ways to implement the resolutions from the Bangalore meeting. This gathering detailed plans for a renewed campaign to overthrow the Communist regime in Kerala. They condemned the Kerala Education Bill, stating it contained unacceptable clauses that excluded private educational institutions. The conference passed a resolution appealing to Catholics, recalling with pride the widespread agitation following the bill’s enactment and urging continued and intensified efforts to amend the Kerala Education Act’s “harmful provisions.” (Deepika, March 20)

Justice V. Krishna Aiyer, who served as Law and Justice Minister in the first CPI government, later wrote in his memoirs about the Church’s activities during this period. The Church had formed a riot volunteer corps named “Christopher,” modelled on the RSS. These groups received training in parish premises, learning how to orchestrate acts of violence.

The Catholic clergy had not recently begun their opposition to progressive change. They had actively worked to defeat Communist candidates during the elections, mobilising Catholic voters against them by claiming that religion and the Church’s interests were threatened under Communist rule. Places of worship were turned into election platforms, and religious sentiments were exploited for narrow political gains.

Priests resolved to “take necessary steps in cooperation with other communities” and embraced Mannathupadmanabhan, who had previously opposed them. This marked the emergence of a new alliance spanning Hindus, Muslims, and Christians, united in opposition to the Communist government.

On the third day of the clergy conference in Ernakulam, March 20, the Kerala Private School Managers Association Action Committee met at Perunna. Mannathupadmanabhan, the influential leader of the Nair Service Society (NSS), was elected president of this committee, Father Mannanal as convener, and Sri V.O. Abraham as treasurer. Initially a supporter of the Education Bill, Padmanabhan switched allegiance after the Agrarian Relations Bill was introduced. Landlords from various religious backgrounds joined forces against the progressive government.

Mannathu Padmanabhan’s own words illustrate this struggle:

“We have to raise lakhs of rupees. Committees must be organised everywhere. Many efforts are needed… We are entering a war zone. Caution is essential because we are fighting the communists… We do not believe they will retreat without a revolution.” (Deshbandhu, May 5)

Deepika’s editorials also advocated for secret groups to be formed locally and urged preparations for an uprising “at any material cost.” Calls for violence against the Communist government echoed through Catholic churches, urging supporters to take action.

CIA and Global Capital Involvement

Declassified documents from the CIA and National Security Council, released in the early 2000s, have rekindled debates about American interference in Kerala’s politics during the late 1950s. These documents suggest the United States covertly worked to destabilise India’s first democratically elected communist government in Kerala. Upon the CPI’s rise to power in 1957, the U.S. viewed this as a strategic threat. A National Security Council briefing in May 1957 noted that if the Kerala communist government succeeded, it might inspire similar movements nationwide. The U.S. feared that economic progress under the CPI would increase communism’s appeal across India.

Reports claim that the CIA funnelled funds to the Congress party and opposition groups to organise protests and strikes. Ellsworth Bunker, then U.S. ambassador to India, allegedly collaborated with Indian intelligence and provided funds to Nehru’s Agriculture Minister, S.K. Patil, to fuel anti-CPI agitation. Historian Paul McGarr, in his book The Cold War in South Asia, supports these assertions, stating that President Dwight Eisenhower authorised a covert CIA operation to undermine the CPI government.

Ravi Raman, former Kerala State Planning Board member and author of Global Capital and Peripheral Labour, recounts:

“George Soutar, acting General Manager, approached Prime Minister Nehru via the offices of UPASI president M.M. Varghese and W.C. Roy, convincing the Central government that Namboodiripad’s government must be terminated. Consequently, 28 months after taking office, the President of India dismissed the ministry on July 31, 1959, and installed a caretaker administration under the state Governor. Colonel Mackay later described this as Namboodiripad’s ‘Waterloo’ in the High Ranges.” (Page 148)

Conclusion

To conclude, it is important to highlight the slogans used by the Congress-led right-wing factions against CPI leaders. These slogans expose the crude, casteist, and classist nature hidden beneath the moralistic facades of these groups. Such rhetoric clearly demonstrates that Congress and right-wing forces have no legitimate claim to the progressive legacy Kerala experienced during the renaissance. The CPI leaders’ only “offence” was their attempt to build a prosperous and equitable state.

“Manda munda Mundasserry, ninte mandayil entha kalimannanoe” (teasing Prof. Mundasserry),

“Keram thingum Kerala nattil K.R.Gowri bharikenda” (K.R.Gowri should not rule Kerala, the land of coconut)

“Pallel kanji kudippikkum Thambran Ennu Vilippikkum (Will make you drink gruel in leaves laid on the ground and make you call us “lord)

“Gowri Choththi pennalle pullu parayakkan poykoode (KR Gowri is an Ezhava women, why can’t she go pluck grasses and live)

“Chaaththan poottan pokatte.. Chacko Nadu bharikkatte” (Let Chathan/Chathan master the tall leader of Dalits and oppressed go plough the field while Chacko (Congress leader) rulesw the state)

Undoubtedly, the dismissal of the first CPI government was a clear misuse of the Constitution, and this event triggered a series of such misuses throughout the modern history of India.