Vast sections of the world’s population are inspired by the same desires and live for common interests that bind them together far more than they separate them.

– Mikhail Sholokhov

A second opinion never hurts, not only in medicine, but also in politics.

– Sergei Lavrov

Soviet literature is a phenomenon in world literature. I came to know Soviet literature in 1961, when I read in an American news magazine about the Soviet journalist and poet, Ilya Ehrenburg and his important work, The Thaw (Russian: Оттепель, Ottepel). I remember standing on the corner of Douglas Avenue in Wichita, Kansas, reading about the book that had brought controversy and further enlightenment about life in the Soviet Union. I ordered the book which came from England. I had been acquainted with Russian literature since the age of ten or eleven years old when I read War and Peace by Tolstoy due to crises I was going through regarding the early death of my father, Luis Garcia Tijerina, who was a labor contractor and who had written poetry during his short life. I had yet to be acquainted with Soviet literature whose roots would be the literary observation called social realism.

Later, when I joined the United States Army and was an ordinary soldier in the Fourth Infantry Division at Fort Carson, Colorado, I read the great satirical work by Ehrenburg called The Extraordinary Adventures of Julio Jurenito and His Disciples which begins in Paris, and which involves the narrator, Ilya Ehrenburg, who is the first disciple of the frantic Jurenito, a wild Mexican artist. Ehrenburg follows his mentor in his escapades across Europe as they observe the European bourgeoisie after the World War I. Both mentor and disciple comment on the decaying Western European cultures with vivid sarcasm and satire. It was only when I enrolled at Kansas State University in 1964 through an athletic scholarship, that I began to experience Soviet literature from beyond a personal and subjective experience to a more objective observation of the galaxy of Soviet authors that had been translated into English and which would transform my intellectual, political and literary life with consequences. As Domenico Losurdo, whom I attempt to emulate, wrote about his communist beliefs as a political historian, “As a communist – and not only that, but also as a philosopher and historian – I am going to fight and continue to fight the dominant ideology. For the dominant ideology is a manipulation of history and an obstacle to the process of emancipation. And we, for our part, have to rethink this process itself.”

I will explore in this essay how the dominant ideology in the West, particularly in the United States which with its Russophobia has never been able to accept the profound intellectual legacy of Soviet literature. Through sharing my own life of reading the great Soviet literary works and how they influenced me, I would like to attempt in a limited way to undo some of the manipulation of anti-American ideology that has sought in the most condescending of ways to do away with the culture and political forces that Soviet writers brought forth to the world community after the October Revolution under the auspices of Lenin’s leadership.

Soviet literature provides a profound experience in the literary observations of dialectical contradictions within the human community. In my time as an undergraduate, during which I majored in philosophy but later switched to European Intellectual history, I read both Soviet poetry and Soviet novels, when I was not studying or running cross-country and distance events in track and field. Later in life, when I became a Football coach, known in the United States as a “soccer coach”, my youthful studies of Soviet literature served me well in understanding the social and class issues and contradictions that I observed in those I coached.

There is among the Left and Right critics and readers in the United States with naïve, and even romantic interpretations, of Soviet writers, thinking that they all came more or less from working class origins or that the majority of them were persecuted by the Soviet State or that their flaws as people and writers were minimal which was not the case. A few of them suffered from some form of mental illness like the peasant poet, Sergei Yesenin, who grew up in a village on the Oka River in Russia, and whose poetry breathed the earthiness of Russia and a deep longing for his peasant roots. Driven by alcoholism and mental health issues, he hung himself at the age of thirty. Vladimir Vladimirovich Mayakovsky, the most revered poets of the Soviet Union was born in 1893 in Baghdati, Kutais Governorate, Georgia, which was then part of the Russian Empire. Unlike Yesenin, he had a messianic vision of the creation of the Soviet Union, but was imprisoned in his own way by not understanding the economic and political stages that would be difficult but necessary for the Soviet Union to go through at the beginning of the twentieth century. With the suicide of Yesenin, Mayakovsky chose to follow him into a similar death by shooting himself. There was an important commentary made by Mayakovsky’s great Swedish biographer, Bengt Jangfeldt, who quoted from correspondence with Mayakovsky’s lover, Lili Brik –

“How many times did I not hear the word ‘suicide’ from Mayakovsky,” Lili wrote. “That he would take his own life. You’re old at thirty-five! I shall live till I’m thirty, no more.” His terror of becoming old was closely connected to his fear of losing his attraction for women. “Before the age of twenty-five a man is loved by all women,” he stated shortly before his suicide to a twenty-five-year-old fellow writer. “After twenty-five he is also loved by all – except the one he is in love with.” …

However, it was the American literary critic, Cynthia Haven, who, perhaps, understood the deeper ramifications of a messianic response to the Russian Revolution and the evolution of such a great and conflicted poet by stating “Mayakovsky was a maximalist: he gave all that was in his power and demanded much in return…Love, art, revolution – to Mayakovsky, everything was a game with life as the stake. He played as befitted a compulsive gambler: intensely, without mercy. And he knew that if he lost, the result was hopelessness and despair”.

I remember in my thirties or, perhaps, early forties, I came across a comment by Lenin where he more or less stated that studying Marxism does not solve one’s personal problems, but what it does do is raise one’s class consciousness about one’s existence within an economic and political situation.

In addressing the subject of Soviet poets and human tragedy, one cannot forget the great poetess, Marina Ivanovna Tsvetaeva and the poet, Osip Mandelstam, both Russian and Soviet poets. In life, neither of them called themselves a “Soviet poet” as they did not desire to support the political and cultural policies of the Soviet Union. Tsvetaeva went into exile in the cities of Berlin, Prague and Paris, before returning eventually to the Soviet Union. The Soviet authorities were harsh on Tsvetaeva. Eventually, she was exiled to Yelabuga, a town in the Republic of Tatarstan, and she ended her life by hanging herself in a barn. Now, in post-Soviet Russia there are museums in her honor, and she is considered one of the Soviet Union’s greatest poets. In the later stages of my mid-life, I read Tsvetaeva’s poems continually and even bought English translations of her books to give to my friends.

As for the Polish Jew, Osip Mandelstam, although I would say he was a great poet, I would say that many of his poems are elitist in nature and reactionary in relationship not only to the Soviet state, but to ordinary people in general. Mandelstam’s most serious insult to the Soviet Union was in the autumn of 1933, when the politically White poet composed the poem “Stalin Epigram” which he read at a few small private gatherings in Moscow. The poem deliberately insulted the Soviet leader Joseph Stalin, and it would have severe repercussions.

Stalin was personally and politically furious and telephoned Boris Pasternak, another famous Russian and Soviet poet, asking him what he thought of Mandelstam’s poetry. Pasternak was not a very brave man. He abandoned his friend, and did not give his support to the poet, except to acknowledge that he did not approve of the poem. Stalin was silent, and then hung up on him.

I should mention that it was the great Russian and Soviet symbolist poet, Alexander Blok, and the poetry of Pasternak, especially his work, MY SISTER – LIFE that influenced my own poetry during my mid-life. At certain periods in my life, I wrote love and nature poems that were inspired by Pasternak. Later, Mandelstam would be sent into exile with his wife and eventually to various labor camps. On December 27, 1938, three weeks before his 48th birthday, Osip Mandelstam died in a transit camp of typhoid fever. Osip Mandelstam’s body lay unburied until spring, along with the other deceased. Then, the entire “winter stack” was buried in a mass grave. His demise was much different and more of a political death than that of the poets, Yesenin and Mayakovsky.

Mandelstam’s death was an unconscious suicide due to his entrapment in his political beliefs as he represented a wealthy Jewish family, and he also was close to the Socialist Revolutionary Party. Mandelstam’s poetry was also very acutely populist in spirit after the first Russian revolution in 1905, and, therefore, like all great poets, he was a poet of profound contradictions. I have given, but a few examples of the Soviet Union’s great poets, although there other Soviet poets like Andrei Voznesensky, who was a daring and highly prolific poet. I remember in my twenties reading his poem “I am Goya!” His poem, in part, reads –

I am grief/ I am the tongue of war/ the embers of cities / on the snows of the year 1941

The Soviet poets, not unlike other poets in the modern world, revealed more than their share of personal and political contradictions, and although this essay does not do justice to their private griefs, their personal literary achievements have their place in the lexicon of the Soviet literature.

If I am to be very honest with the reader, I must admit that it was not Soviet poetry, but Soviet novels that played a role in my prose work from the time of my youth to old age. At Kansas State University, I began to read all the Soviet novelists’ works in English translation that I could get a hold of, obviously at the expense of my studies, but not my athletic endeavors.

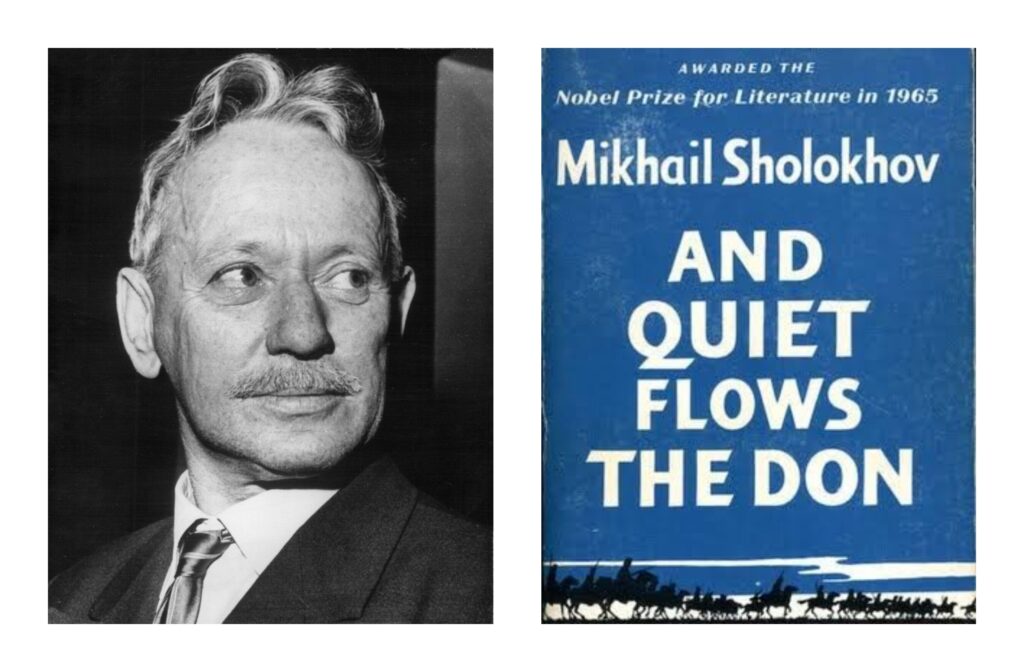

I read Mikhail Sholokhov’s famous novel, And Quiet Flows the Don. In the same year after Sholokhov completed, And Quiet Flows the Don, it won him the State Stalin Prize in 1941 and the Nobel Prize in 1965. This epic work is about the lives, tribulations and social victories of the Don Cossacks before and during World War, the Russian Revolution, and the Russian Civil War. In the Don Cossack region in Russia, I found an equal in my imagination in the prairies and vast wheat fields of Kansas. In my daydreams, I found myself galloping by horseback like a Cossack with a sword and Winchester rifle in my hand, fighting an imaginary invader as if the prairies were the steppes of Russia. Historians have actually compared Kansas with regions of Russia and the Ukraine. The book, in some ways, explains why I was drawn to Leo Tolstoy’s The Cossacks in my teen years. Both the Russian author, Tolstoy, and the Soviet author, Sholokhov also influenced my interest in military history and my choice to become a soldier later in life.

In the 1920’s, there were allegations of plagiarism by Sholokhov, and the allegations resurfaced again in the 1960’s. In the 1920’s, the allegations were discredited because a draft of volume four in his own handwriting of Sholokhov’s novel survived World War II. These allegations played into the hands of the American literary critics and government to attempt to discredit Sholokhov and his masterpiece. The Soviet and dissent author, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn accused Sholokhov of plagiarism, possibly in retaliation for Sholokhov’s harsh criticism of Solzhenitsyn’s novella One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich. In 1984, Norwegian Slavicist scholar and academian mathematician, Geir Kjetsaa, in a monograph written with three other Norwegian colleagues, provided statistical analyses of sentence lengths showing that Mikhail Sholokhov was likely the true author of And Quiet Flows the Don.

And finally, in 1999 the Russian Academy of Science carried out a thorough analysis of the written manuscript and came to the ultimate scholarly conclusion that And Quiet Flows the Don had been written by Sholokhov himself. A lengthy analysis by Felix Kuznetsov revealed the creative literary process visible in the papers and provides detailed support for Sholokhov’s authorship. The reader may wonder why I have gone into some detail about this particular literary masterpiece. I would say that accusations by Solzhenitsyn stemmed from anger because his work was criticized by a notable Soviet author. The dissident Solzhenitsyn was an admirer of Franco and eventually Pinochet, because both men murdered or tortured communists in their individual countries. Whereas Sholokhov was a committed communist to the end of his life, Solzhenitsyn, would move to the right as something of a nationalistic and religious bigot who reveled in the demise of the Soviet Union. However, I will state that his work Cancer Ward is one of his finest novels and from my perspective the work redeems some the hacked work he produced about the history of World War I and his inaccurate history of the Soviet Union’s prison camp system from 1918 to 1956.

Both Soviet novelists reveal the deep political contradictions that existed in the Soviet State, which in the post-Soviet period is now known as the Russian Federation. The jealousies and bitter literary disagreements between American novelists, that are so prevalent in capitalist nation-states where fame, money and dominance by mainstream writers is everything, Ernest Hemingway and William Faulkner, for instance, are what one would call child’s play and immature behavior in comparison to the Soviet class and political differences between the various Soviet novelists.

Another important Soviet novelist, Konstantin Simonov, was an important influence on me during my time in the United States Army. On field maneuvers, I read his greatest work The Living and the Dead which was actually part of a trilogy. The story centers around the Soviet political instructor, Sintsov, and how he copes not only with the brutality of the retreat from the German Nazi forces, and the reality that is wife might have perished behind the lines as well as his struggle with his patriotism for the Soviet Motherland even as his communist party card has been taken from him for his political dissent. Simonov, who was a war correspondent and eventually a full colonel in the Soviet Army, was able to portray war in very lucid detail. He is one of the Soviet authors who have written about the complexities of war that should be studied by military historians to grasp the reality of the psychological torments and private aspirations of the common soldier, especially in a war of Liberation, in the ultimate defense of the Motherland, and in giving one’s life if necessary.

Simonov occupies a unique place in Soviet literature in that he offers an important perspective of an actual Soviet soldier’s life who served in combat in contrast to other Soviet writers who wrote about the Great Patriotic War from a civilian perspective. Simonov was extremely accomplished in that he also wrote truly moving poems like the classic Wait For Me, which he wrote during the siege of Odessa when he faced certain death, with the last stanza ending –

“Wait for me and I’ll come back / Escaping every fate! / ‘Just a lot of luck!’ they’ll say / Those that didn’t wait. / They will never understand/ How, amidst the strife / By your waiting for me, dear / You had saved my life! / Only you and I will know / How you got me through! / Simply – you knew how to wait! / No one else but you!“

Konstantin Simonov was a poet like no other when the Soviet peoples were fighting for their very existence, and his poetry is historically important for understanding the deeper griefs of the Soviet people whose loss was from twenty-nine to thirty million Soviet citizens and armed forces personnel during World War II. Americans could never fathom such a historical tragic loss in world history, except to some extent, those who experienced the American Civil War.

I shall mention a few more novelists which I read in my youth and later years whose works I cannot forget – Maxim Gorky, Aleksey Tolstoy, Vasily Grossman, and Konstantin Paustovsky. At Kansas State University, I read Gorky’s Tales of Italy which I compared to some extent to Stendhal’s short novels on Italy. Though Gorky wrote about ordinary people’s lives and the sublime Italian landscape, whereas Stendhal wrote about the Italian aristocracy and its intense struggle for dominance by class and its torturous relationships. Alberto Moravia’s Roman Stories were similar to Gorky’s short stories. Although I would say that Moravia’s stories were more realistic about the Italian proletariat’s lives in the often-brutal quarters of Rome, while Gorky had, to some extent, a romantic view of Italy although that romance with Italy was sincere in nature. I mention the French and Italian writers in reference to Gorky’s short stories, as all three writers were universal in their study of the human condition in Italy and beyond. It has become more apparent through the years of my life how universal the Soviet literary landscape is in relationship to world literature.

When I was stationed in West Germany as a Vulcan artillery crewman, I devoured the works of Aleksey Tolstoy and Vasily Grossman. I read A. Tolstoy’s Peter the Great which I consider to be one of the most important historical novels within Soviet literature. He brought Peter the Great alive for me. I came to know the beginning of the political power of Russia from the time of Peter the Czar to the present time in Russia, and how it is one of the greatest political states in the modern world.

I have before me a copy of Vasily Grossman’s Life And Fate which is difficult to read because it is one of the few modern works about warfare written in an almost Chekhovian style where each chapter is a story in itself. It is detailed in the most matter-of-fact way that brought emotional shivers to me. As a military historian and theorist by education, I rarely accept novelists who write about war, specifically a writer like Hemingway who romanized the Italian front in World War I with his work A Farewell to Arms and his Spanish Civil War novel For Whom the Bell Tolls. I know that many Soviet citizens naively admired the works of Hemingway which I can understand as his macho literary language was understood by the more conservative Russians and Soviets who read the great novels by Isaac Babel who wrote the brutal but realistic work, Red Calvary. Both writers presented soldiering and war as a bigger than life encounter without always acknowledging that war is a harsh business that kills without mercy the poor, the old, those with disabilities and innocent children. With Vasily Grossman, it was different, for he burrowed into the physical, human emotions and psychology of human suffering that took place at the Battle of Stalingrad.

However, one could also argue that his war journalism during the Great Patriotic War, also known as the Second World War, was more powerful in the way he interviews the common Soviet soldiers and generals whom he met and who were not afraid to open up to him because of his genuine interest in their lives and even their subsequent deaths. I have thought more than once that Grossman was a far greater war reporter than Ehrenburg as I feel that Ehrenburg’s lasting writing can be found in his historical works, Memoirs: 1921-1941 and Post-War Years: 1945-54 which influenced me in writing my unpublished manuscript, On Leave In Paris as well as some of my political essays.

Finally, I come to my reading of Konstantin Paustovsky’s great masterpiece, The Story of a Life which has moved me for very personal as well as political reasons in terms of being what one might call an orthodox Marxist Leninist, but a Marxist Leninist who has more in common with the Italian Marxist political philosopher, Domenico Losurdo, and to a smaller extent, with the Portuguese communist novelist, Jose Saramago.

What I admire about Paustovsky’s autobiography was the way he described his father’s death at the beginning of the work and then slowly begins to give the reader his life as a youth, his escapades in the gymnasium, his first love affair and then the tumultuous and violent life that surrounded him during the Russian Civil War. I can still see his sister who is blind and still continues to want to live with her mother even during their most deprived times when the various political forces brought both mother and daughter to poverty, how Paustovsky was tortured and hurt, and could not help his mother or sister in their utter poverty. Lelya, his love, during the Russian Civil War who died at the front from typhoid in a small, deserted hut, said in her dying words to Paustovsky “… my only joy, you mustn’t cry. I‘ve forgotten everyone, even my mother… only you…” I understand that in the country I was born into, the United States of America, uncommonly are such sentiments recorded in the history of a man’s or woman’s life who has known loss in one’s own homeland that can be unspeakable in a time of war. The American writer, Stephen Cranes’, Red Badge of Courage, is a profound exception because he showed the sorrow, courage, and horror of war in the United States of America. I have found that it is among the American colonized writers that one perceives the sensitivity and tenderness about the complexities of life and death. It was Paustovsky’s autobiography that helped me write a poem about my father’s death.

THE RUSSIAN WAY

For my father, Luis G. Tijerina,

who died on October 17, 1956

On an October day, I stood before your casket/ a white satin lining surrounded your body clothed/ in dark pants, beige sport coat and scarlet tie/ Your hands folded firmly as if sculpted/ from the finest, soft stone/ There were large red candles flickering/ at the corners of the open casket./ Icons of saints and the Virgin of Guadalupe/ surrounded by colorful flowers and magenta mountains/ enclosed the humble living room/ The women cried unconsolably/ when standing before your silent face/ your eyes closed forever at the funeral wake/ the chill wind breaking through the front door/ I kissed your forehead, Father, and it was cold/ And then I knew, as a young boy/ I also would someday become cold like stone/ and that’s it.

Even in old age, Paustovsky has helped me to understand loss through Soviet literature. There will be for many generations serious intellectual debates about the historical place of Soviet literature within the literary cannons of world literature. I have never shied away from Soviet social realism, but being born into a capitalist and imperialist nation like that of the United States, I have failed in my writing to see my country as it actually is which is tragic and rooted in the exploitation of colonized peoples and whose main dominant culture, Anglo-American, is racist, both consciously and unconsciously, in its social and political intent toward other races.

However, the task of the writer is to not only expose political excesses that are cruel, barbaric and even insidious in all their evil banality, but to also write about the human condition as Ilya Ehrenburg once wrote, “There are certain events that it is hard to ignore. You can’t sleep through wars; sirens or summonses are sure to awaken you. A storm topples the trees. If a neighbor dies, his body is carried out of the house. The newborn babe cries on the other side of the wall. But an artist must be able to hear the grass growing, for that is why he is an artist” In a few words, Soviet literature taught me how people live and die. I must hear the grass growing even as I also know that someday I will no longer write, and another writer will write about the grass growing over me.